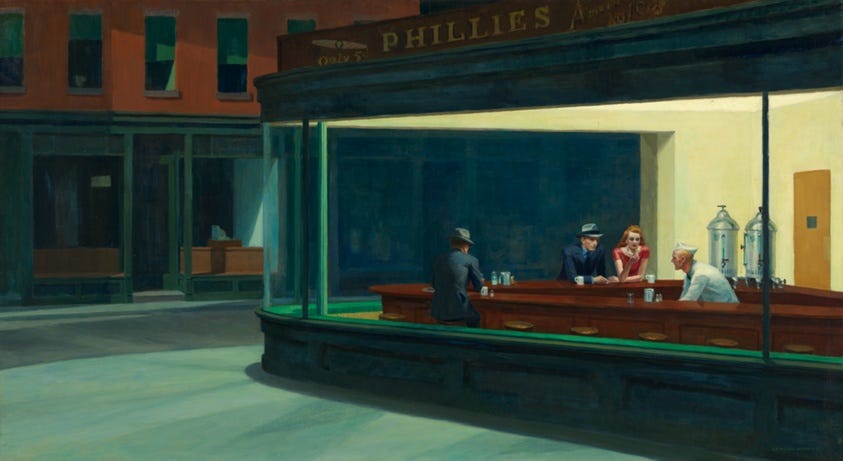

I kept seeing a clip passed around of a Google Gemini demo that lets you walk into Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. I clicked because the painting is not abstract to me. It is a landmark in my daily orbit. I have lived by the Greenwich Avenue corner for more than thirty years, and the composition sits in my head like a set of angles I know by light. The demo…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Analyzing Trends to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.